Hunger has many different faces and is a truly global problem. The world population experiences hunger in more ways than previously thought. Climate change is only making it worse. Read more in this instalment of The Food Diaries mini-series.

The two faces of hunger

Hunger can become visible in ways, which seem opposite to each other. Society is (unfortunately) used to seeing the face of hunger. However, we more often relate hunger to food shortage and too few calories available. Yet, too many calories can also lead to hunger. The density of energy in food does not reflect how nutritious it is and this is an important distinction. As bad as “empty calories” are, a bigger danger for our health related to what we eat remains often unseen.

Malnourishment

Obesity

From the two graphs above, it becomes immediately clear that obesity and malnourishment are the two sides of the same coin – shortage of nutritious food. We are collectively producing almost 2,5 times more food (Complete report by Worldmapper) than we did only half a century ago. However, it seems that this food contains less quality nutrients than before.

Impact of climate change on hunger

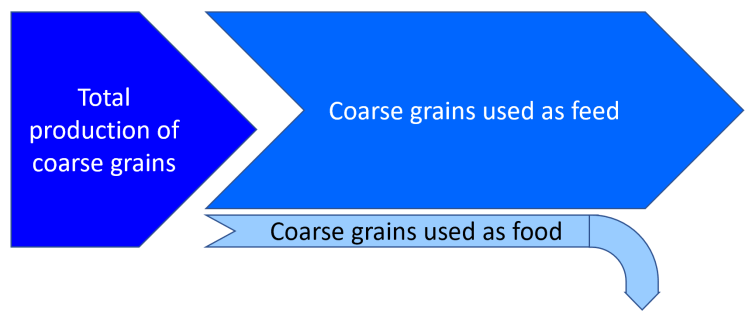

Some crops, however, fail more rapidly than others under worsening climate. Such crops include, but are not limited to, maise, oats, barley, and millet. They predominantly feed livestock, which only makes the knock-on effect of yield losses worse.

At the same time, the demand for meat production is continuously growing. The global projection shows growth of production of farm animals by 50% by 2030, compared to 2010.

Our crop yields are expected to decrease due to climate change. Our meet production demands are expected to grow. We will have to be feeding more animals with less food if both those trends are met. This math simply wouldn’t work!

Decreasing key nutrient content = hidden hunger

Other crops, like rice and wheat, are susceptible to decreasing nutritiousness, even if their mass yield remains stable. As if slowing yield increase due to worsening climate is not already a complex enough problem to solve!

A recent review from The Business Insider, summarises data reports on the risks of growing major staple crops in worsening climate.

Carbohydrates, energy, and other organic molecules, are product of photosynthesis – the conversion of CO2, water, inorganic salts and sun radiation. The claim that increased CO2 leads to higher plant production was rebutted by many, large-scale peer-reviewed studies. Example for one of these is by Pérez and colleagues, it also contains references to many of the other studies. Plant physiology is much more complex than climate deniers believe it to be. It includes many feed-back loops and metabolic sideways, which do not allow for simple “increase input=increase output” type of production.

Insufficiency of key nutrients in our food can lead to health threatening conditions as hunger does. Iron, iodine, and zink are just a few of the vital microelements, which are depleted very quickly from the soils with the increased rates of photosynthesis. In an exhaustive study involving scientists from three continents, in almost all 40 different cultivars (shared between corn, legumes, and grains), iron, zink and protein content are all significantly decreased at higher CO2 content.

Food produced from poor-nutrient raw materials is often rich in calories, but insufficient in key elements. As a result, consuming such foods, leads to obesity combined with malnutrition – a deadly combination of conditions for both children and adults.

More on the topic

- FAO 2019 report on the world’s food security and nutrition;

- Data from the European Union on Global Hunger Index;

- UN News bit on the worsening food quality due to climate change;

- Agriculture, while negatively impacted by climate change, is also one of the main contributors – a study on the impact on climate of what and how we eat it;

- In some cases, biofortification and biotech breeding can prove useful to combat the decreasing nutritional richness of food;

- A study reviewing the societal burden of hidden hunger.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)